It’s Beginning to Feel a Lot Like Flu Season

Part 1: History & Development

By Bonita Banks, BSN, RN, CRNI

Health & Wellness Educator for South Peninsula Hospital

Annually, influenza viruses are active in the United States during late fall through early spring, and most people who get the flu will recover without complications. Unfortunately, influenza can also result in more serious illness and even death. Older adults, very young children, pregnant women and people with chronic disease are those at greatest risk of more serious complications from the flu. For people 6 months old and older who do not have contraindications, the influenza vaccine is the primary means of preventing the flu and its possible complications.

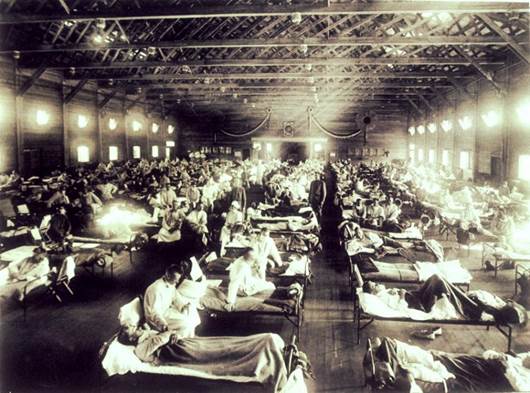

History

Before isolation of an influenza virus in 1933 and consequently the first flu vaccine, the world experience the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, which infected an estimated 500 million people across the world, and resulted in an estimated 20-50 million deaths. At the height of the pandemic, people died within hours or days of experiencing flu symptoms. Also known as the Spanish Flu due to the high number of deaths in Spain early on in the pandemic, there were few places the virus did not reach. In 1918, the town of Brevig Mission, Alaska (outside of Nome) had a population of 80. 72 people in Brevig Mission died from influenza that year.

Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine

The initial influenza vaccine developed was the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which works by introducing a weaker (attenuated) form of the live virus into the body. The body will recognize the virus as foreign (antigen) and as an immune response will develop antibodies against it. If exposed to the virus again, the antibodies will aggressively attack it to prevent illness.

This type of vaccine is administered only as a nasal spray and has been approved by the FDA for use in people ages 2-49 who are not pregnant. Advantages include eliciting a more natural immune response in the body with potentially longer lasting effects. The LAIV has some disadvantages, including not being a good choice for people with weakened immune systems, and they must be kept refrigerated to keep the virus alive. It is also necessary for the live virus to replicate in the upper respiratory tract for the immunity to develop as needed.

Inactivated Influenza Vaccine

In the early 1940’s, inactivated flu vaccines were developed and became the vaccine most commonly used. As the name suggests, the virus has been killed (inactivated) but generally will still induce the desired immune response in the body. They are considered safer for anyone with compromised immune systems, and are also much easier to store and transport, as constant refrigeration is not required. This can be given as an injection into the muscle (intramuscular), or as an injection into the skin (intradermal).

Recombinant Influenza Vaccine

Approved for use in the United States in 2013, this technology is not an egg-grown virus, but uses an isolated protein from a naturally occurring virus that will elicit an immune response in humans. It is combined with other virus proteins and grown (replicated) in insect cells. The needed proteins are then harvested, purified, and sent to the FDA for testing before being approved for use. At this time only one influenza vaccine using this method of production, marketed under the name Flublok®, and it is approved for people 18 years and older and is safe for people with any egg allergies.

Seasonal Vaccine

The two types of influenza virus that cause epidemics in humans are influenza A and B. Based on characteristics of surface antigens, the A viruses are divided into subtypes, and B viruses into lineages. New strains or variants develop as virus mutate.

Strains of influenza that have occurred during the flu season in the Southern hemisphere are examined during February of each year by an expert panel. Predictions are made for the expected strains that will be seen during the Northern hemisphere’s upcoming flu season. The seasonal influenza vaccine can then be representative to reflect those particular strains. Produced primarily in embryonic chicken eggs, it takes approximately 6 months for the vaccine to be ready for use. Because of this lag time, it is possible for a variant of a virus to develop and not be represented in the vaccine.

A trivalent (three part) vaccine traditionally includes two influenza A viruses (H3N2 and H1N1) and one influenza B virus. A quadrivalent (four part) vaccine has also been developed and made available with a second type of influenza B that has circulated. Once the vaccine has been introduced into the body, it takes about 2 weeks for the antibody response to reach its peak. Although strength of the antibody response weakens over time, after 6 months the levels appear to continue to be protective.

References:

- History.com – 1918 Flu Pandemic

- University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute – Villager’s remains lead to 1918 flu breakthrough

- NCBI – Influenza Vaccination Strategies: Comparing Inactivated and Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccines

- Immunization Action Coalition – Ask the Experts: Diseases & Vaccines